Their Memories are Mine

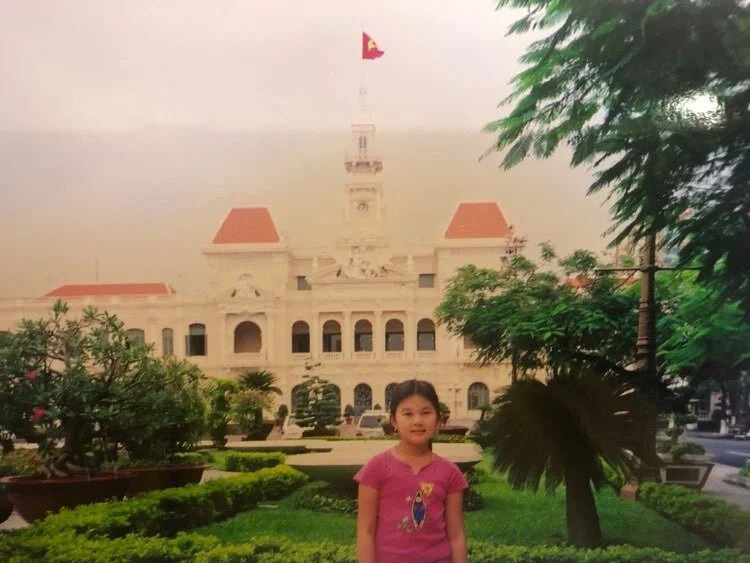

Thu in Saigon, VN. 2005 or 2006, it’s been so long she forgot. Cue this song for bg music.

In the city of Quy Nhơn, located in the province of Bình Định, there were, and probably still are, many fish sauce producers. Because of its coastal location, there is abundant access to anchovies, the key ingredient in nước mắm. Large tanks are filled two-thirds of the way with fresh anchovies and topped off with sea salt. Mother nature (aka fermentation) takes over the process: salt breaks down the fish and the entire tank eventually turns into liquid/salty fish slush. Extraction of nước mắm from the tank happens in stages, each a lower quality grade than the previous. The tanks are tapped at the bottom, and the best quality nước mắm comes out first. It’s practically liquid gold and typically only gifted on special occasions. All of the extractions that follow are lower in quality, meaning there’s less essence of fish, and more so just salty.

As a result, everyone working at nuoc mam manufacturers smell like nước mắm, and nước mắm wafts through the city. You’re either gagging, wrinkling your nose, or salivating right now, aren’t you? But everyone there grew accustomed to the smell, so there weren’t any complaints. One of the city’s main industries nurtured my father’s preference for salty foods and his habit for practically sipping nước mắm out of the bowl after eating bánh bèo.

When I lived alone in DC, I craved nước mắm often and would be transported back to these scenes in Bình Định when I ate or cooked with it. The taste of fresh seafood, the smell of salt and fish in the air, and the wind carrying dust in the roads as my kid father played marbles with his friends: the memories all came rushing back to me.

—-

As the Houston humidity and heat seep back into the city, my mother and I grow increasingly lethargic. Lounging around in our silk or rayon pajamas we brought from Vietnam, we binge Asian dramas and daydream about the various tropical fruits we could be eating. If we’re lucky, we score a decently priced jackfruit at the market to eat for a week, but these days we’ve been settling for just quarters of a jackfruit.

It’s a team effort to eat jackfruit. One person cuts the fruit into quarters and slices, another wipes the sticky sap (this is what causes jackfruit allergies) away, and one or two people separate the ripe meat of the fruit from the surrounding fibers. If we’re feeling fancy, the seeds are also taken out of each piece. Once we’re done, I typically double bag the jackfruit peel because of its spiky points. Just like how the thought of nails on a chalkboard can give you the heebie-jeebies, touching spiky jackfruit peels make my knees ache. I’m reminded of the times when my kid mother was threatened with kneeling on jackfruit peels as discipline in Saigon. I thought I had it bad with carpet or tile flooring…

—-

I was born in 1995 in El Paso, TX. I’ve never been to Bình Định, and I don’t remember what jackfruit tastes like in Saigon. But I can live and experience these childhood memories as if they were mine, and Vietnam (granted, frozen in time, 1970s-1980s) feels like its a part of me too.

As another anniversary of the Fall of Saigon, April 30th, passes by, I reflect again on why it’s important to remember this day. Two years ago, I wrote about how it informs my present-day work. This year, we spend April 30th either alone or with our families in social distancing. While at first, it was a struggle to adjust living and work together under one roof (we don’t all politically align too well), it has become comforting to hear the voices of Khánh Ly, Duy Khánh, Chế Linh, etc. drift through the house as I work. At meals or when I wander into the living room on my breaks, I’m blessed with more stories from my parents’ Vietnam.

When my dad started to crack open the beers and listen to music later into the night, I realized the correlation between the uptick in storytelling to the anniversary of April 30th. The epiphany came along with a deeper understanding of why it is so important for us to remember April 30th. Our identity formation, whether we’re cognizant of it or not, is rooted in culture and our existence as second-generation Vietnam War immigrants. It’s rooted in these stories from our parents, which not only relay their childhood but also our culture and all of its beautiful nuances. Things like eating bánh xèo wrapped in rice paper or poems like Cong Cha Như Núi Thái Sơn aren’t taught in Sunday Vietnamese school or in any sort of textbook on history or ethics. Our culture and history have become oral and are in danger of being lost.

So while we reflect on Black April in quarantine, let us take the time and effort to spend it with family and discovering these precious memories, and make them ours to keep for generations to come.